January 18, 2024.

Theater Review by Carol Rocamora . . .

https://www.theaterpizzazz.com/our-class/

Ten actors take their seats in a semi-circle onstage at BAM Fisher’s Fishman Space, script in hand, as if ready for a reading of a play. But as they begin, they slowly evolve into their characters and reenact dramatically what is undoubtedly the most devastating story you will see on the stage this season (and beyond)—one that will impact you profoundly, one that you will never forget, one must be heard and heeded long after the lights go down three traumatic hours later.

Such is the overwhelming power of Our Class, a 2006 play written by Polish playwright Tadeusz Slobodzianek, telling the story of ten classmates growing up together in the small town of Jedwabne, Poland in the 1930s and 40s. They consist of five Catholics and five Jews. Spanning eight decades, this story reveals how their bonds are torn asunder and their lives shattered and scattered by the cataclysmic historic events of that period, featuring the invasion of the Stalinist Russians, and then the Nazis. Thanks to the brilliant director Igor Golyak, leader of Arlekin Players Theatre, who discovered this play and decided it must be done, the play is the centerpiece of this year’s Under the Radar Festival and it is an absolute must-see for its power and relevance in this time of war and world upheaval.

The play (adapted into English by Norman Allen) is based on a book called Neighbors by Polish author Jan Gross, about a horrific event in Jedwabne, Poland on July 10, 1941, when 1,600 Jews in that tiny town of 3,200 were rounded up in a barn and burned to death. Gross’s research uncovered the truth that it was not the Nazis who executed this terrible massacre—as the Polish government had always proclaimed—but rather the Polish neighbors themselves who grew up alongside the Jews whom they murdered on that terrible day.

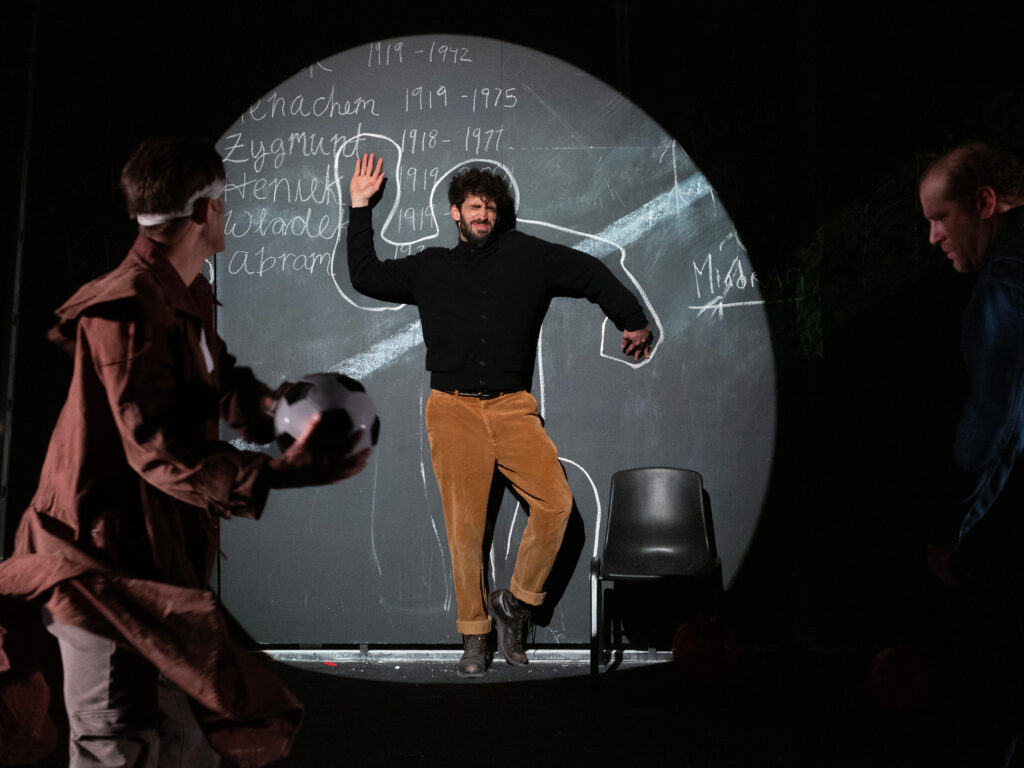

The play is cleverly divided into fourteen so-called “Lessons”—or scenes—that span those eight turbulent decades, accompanied by Polish poems and songs. Act One (covering the mid-1930s until 1941) begins with the classmates introducing themselves. We witness their warm solidarity and mutual affection, laughing and learning together, playing soccer. In Lesson II there is even a mock wedding among the young students between a Catholic boy and a Jewish girl, with everyone cheering “Mazel tov!”

But, starting in 1935, cracks began to form in this solidarity. In Lesson IV one of the Catholic students announces that, by decree of the Polish Minister of Education, Jewish students must sit in the back of the classroom. There are reports of Polish Christians looting Jewish shops and smashing windows. Then comes the invasion of foreign forces, beginning with the Stalinists and their NKVD (police) wreaking havoc on the Polish town and destroying the students’ solidarity. Four of the Catholic classmates (boys) went underground and formed a resistance, accusing their Jewish classmates of Stalinist sympathizing. They accuse one of the Jews, Jakub Katz (played by Stephen Ochsner) of informing on them to the Russians, and beat Katz to death. Next, they rape another of their Jewish classmates named Dora (Gus Birney), who by then had married a Jewish classmate, Menachem, and bore a child.

The chaos crescendos to the horrifying climax in Lesson IX, set on a hot summer day on July 10, 1941. By then, the Nazis had taken over the town and ordered the Poles to round up the Jews in the town square. There, surrounded by an audience of their Polish neighbors who watch and laugh, the Jews are forced by the Poles to weed between the cobblestones, then form a grotesque parade playing Russian songs. The Poles then beat the Jews savagely. Wladek (Ilia Volok), one of the Catholic boys, hides Rachelka (Alexandra Silber), his Jewish classmate, in his mother’s hayloft, but the rest of his Catholic classmates join other Poles in beating, raping, and torturing the towns’ Jews, using axes, knives, and hammers. Dora, clutching her baby, calls out to Rysiek (Jose Espinosa), her classmate, for help, but he hits her over the head with his club. “Everyone was watching,” Rysiek explains to the audience, “What was I supposed to do?” The Jews are then marched to the barn, which is sealed and set on fire. The Polish neighbors watch while 1,600 of their Jewish neighbors burn to death after the classmates help barricade the doors with wooden bolts.

Stunned by the horrific climax, I stumbled out into the BAM Fisher lobby at intermission, incredulous that there could be more of this story that would have as much impact as that first act. But the remaining six scenes (or “Lessons”) in Act Two were also devastating . . . in other ways. They follow the lives of the seven remaining classmates through six more decades, each bearing the indelible mark of July 10. To reveal all these storylines would deprive you of the play’s enormous cumulative impact—but allow me to offer a few in Act Two to give you a sense of the magnitude of betrayal, denial, loss, and personal tragedy. Rachelka has become one of the only two Jews in the entire town to survive the massacre. “You saved my life,” she says to Wladek who has hidden her and agrees to marry him, convert, and change her name to a Polish one (Marianna). The couple is forced to hide during the Nazi occupation, living in the forest (they have one child who died). Still, they live out their days in Jedwabwe; and, after Wladek dies Marianna moves into an old age home, where she spends what she calls the happiest days of her life, enjoying watching TV programs. Another Catholic classmate, Zocha (Tess Goldwyn), hides Menachem (her Jewish classmate, played by Andrey Burkovskiy) in the pigsty behind her house. They, too, eventually marry, but separate as the decades go by (she goes to America; he goes to Israel, where he dies tragically). Meanwhile, Zygmunt writes to his classmate Abram (Richard Topol)—who had gone to America to become a rabbi early on in the play—with the false news that all the Jews in Jedwabne had been murdered by the Nazi Germans.

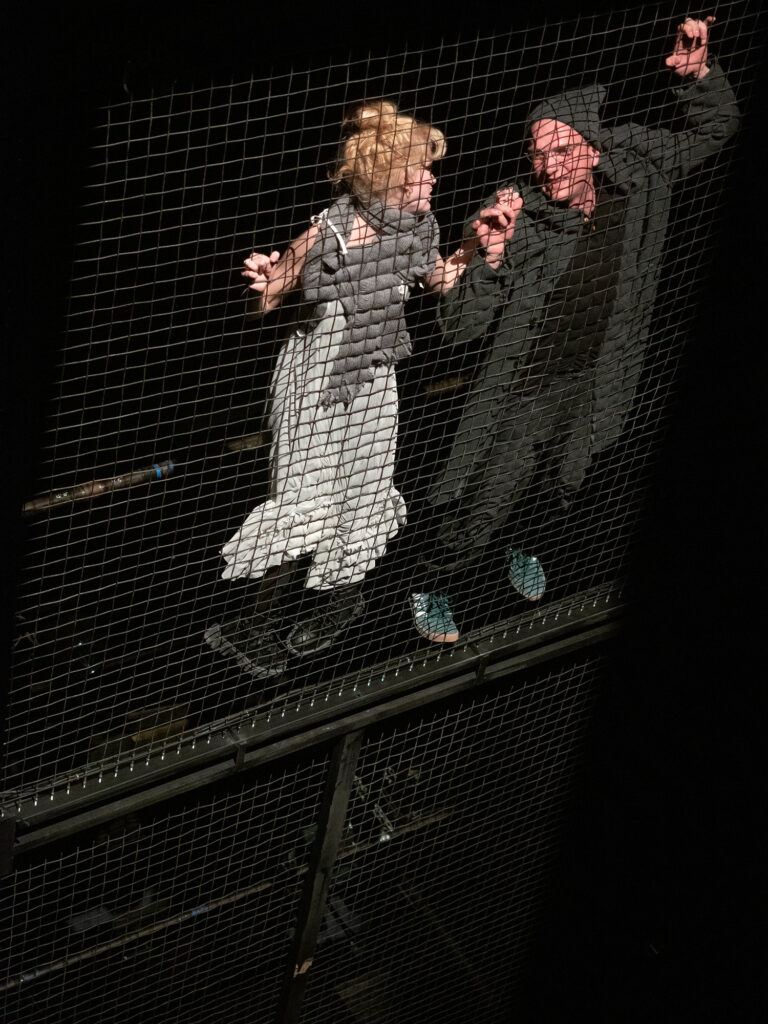

What a huge artistic responsibility it is to put a story of this magnitude on stage—and what a challenge to do it effectively! For this towering achievement, his stunning stagecraft, and brilliant artistry, director Golyak deserves the highest praise and admiration. Together with his gifted designer Jan Pappelbaum, they offer an empty stage flanked upstage by a huge wall that serves as a floor-to-ceiling blackboard on which the classmates write their names and other messages, standing on huge ladders (there are also projection designs on it by Eric Dunlap to illustrate the story as it unfolds.) The blackboard also serves as a backdrop for the violent, vicious beating of one Jew by his Catholic classmates. Director Golyak makes use of the entire theater—at one point, he has actors crawl on platforms hanging from the ceiling. I’ll never forget the culmination of Act One and the image of the Jewish classmates disappearing behind the blackboard which has now become a side of the burning barn, with a terrifying glow of red flames coming from the crack in the floor.

As for Golyak’s stellar international ensemble, they bring each of these characters to pulsating life. (The characters, by the way, are composites based on true residents of Jedwabne.) I’ll never forget the scene dramatizing the horrific rape of Dora (played by Gus Birney) by her Catholic classmates. Dora eventually perishes in the fire; nothing remains of her baby but a crumpled sheet on the stage floor (another one of Golyak’s stunning images). The four Catholic classmates: Heniek (Will Manning), Wladek (Ilia Volok), Zygmunt (Elan Zafir), and Rysiek (Jose Espinosa), though driven to savagery in Act One, manage to elicit our compassion in Act II as history and fate catches up with each of them. Rachelka/Marianna (Alexandra Silber) portrays a young woman dazed to distraction by her fate as the only Jewish survivor of this tragedy (along with Menachem).

According to Rachel Moss, the production’s scholarly dramaturg, Jan Gross’s book Neighbors, on which the play is based, has provoked controversy, causing a debate among scholars and politicians as to the truth of who was really responsible for the massacre on July 10, 1941, as well as the actual number of fatalities. Evidence of that controversy can be found in the village of Jedwabne itself today. According to Sara Stackhouse, the production’s executive producer, she and director Igor Golyak visited Jedwabne and the site of the massacre as part of their pre-production preparation. She reports that the village green featured no sign commemorating the atrocities. As for the site of the barn where the burning took place, there is a plaque saying: “In this spot, Jews were murdered,” with no reference as to who was responsible.

Our Class addresses this terrible and tragic irony regarding truth and history. In the final scene, Heniek cries out to Wladek: “Truth? Which one? There are so many. Pick one. Pick the truth that makes you famous in our old age. Is that what you want? You to rest for all eternity beside the same people whose reputations you destroyed? Your grave next to theirs?” The painful “lesson” we learn from this play is that the obfuscation of the truth happens throughout history. Indeed, we are witnessing it today.

On the production’s website, there is a statement made by actor Richard Topol, who played Abram, one of the classmates who left Jedwabne in the early 1930s. In the play, his character was sent to America and became a rabbi. One of the most heartrending passages in the play is his letter to the Polish government, reciting the names of the dozens of family members he lost in the Jedwabne massacre. In contrast, at the play’s end, he joyously recites the names of his new family members in America—children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Topol’s personal statement on the website resonates like a prayer of hope: “There is always hate in the world, and we have to find a way to overcome that hate.”

Slobodzianeek’s play Our Class had its English-language premiere at the National Theatre in London in 2008. Since then, it’s been performed in Berlin, Tel Aviv, Chicago, and Washington. Now receiving its New York premiere, it plays alongside other productions in response to the rise of antisemitism which have been receiving attention in New York and London. Among these worthy productions, Our Class distinguishes itself with its epic scope and its profound insights into the complexities of history and man’s tragic capacity for cruelty, hate, and destruction. It is also unforgettable for the stunning theatricality and artistry that director Igor Golyak has brought to this powerful work, ending in a startling, moving image of unexpected hope—that of those young classmates at the beginning of their school years together, playing a game of soccer, Christians and Jews, side by side. Despite all this tragedy, the play and its director are bravely saying that hope . . . is still possible.

I couldn’t imagine this story in the hands of a more inspired and creative theater artist than Mr. Golyak. This is a play and production that must be seen—indeed, cries out to be seen in these terrible, troubled times of global strife. It has arrived just at the right moment for us to learn its lesson if only we can.

Our Class. Extended Through February 11 at BAM Fisher’s Fishman Space (321 Ashland Place, between Lafayette Avenue and Hanson Place, Downtown Brooklyn). www.ourclassplay.com

Photos: Pavel Antov